I first learned about the WW2 secret death camp at Sobibor in Eastern Poland from the 1986 film “Escape From Sobibor”.

As trainloads of Jews and other people destined for elimination arrived at the camp’s train station, a few were picked out of the lines to work for the Nazi soldiers and the guards. One of the groups selected were teenage girl knitters. These knitters were among the few spared from immediate death.

Just 42 prisoners of the hundreds of workers at the camp survived from around 300 who escaped during the uprising on 14th October 1943, and among those forty-two were four of the dozen knitters. Thanks to the film “Escape from Sobibor” the world learned of the camp and its prisoners. We now know the story of these four knitters and what happened to them.

The four survivors, Esther Raab, Hela Weiss, Regina Zielinksi, and Zelda Metz had worked together in Staw-Sajczyce, a Nazi forced-labour camp. They were all sent to Sobibor in December 1942 when the camp was built and ready for its grim task. They lived in a hut apart from the other prisoners because the soldiers did not want their socks contaminated with lice.

Hella, was only eighteen when she arrived, and later recalled that day:

“We went through a deep forest, and then we saw a sign [that] says Sonderkommando [a squad of Jews ordered to build the camp who, when it was finished, were shot]. As in a dream, I heard a voice of one of the Germans say: “Who can knit?’ and I stepped out of the line… . The German ordered me to come forward, and then they took me to a cabin, where I found two girls whom I knew before: Zelda and Esther. In my childhood, my mother taught me how to knit socks, so my job was to provide socks for the Germans and to iron the shirts of the S.S. men.

After her escape Hella fought with the partisans and in the Russian army. She received six decorations for fighting against the Germans including the Red Star. In Czechoslovakia she met a Jew in General Swoboda’s army, whom she married and they settled in Israel. Hella died in December 1988 in Gedera, Israel.

Esther Raab moved to the USA after the war, and one day with fellow-escaper Samuel Lerner, Estera recognised SS-

Zelda Metz, after escaping during the revolt, hid with peasants. She obtained false papers stating she was an Aryan and she worked as a nanny for a family in Lwov, finally settling in the United States of America in 1946.

After the war some of the survivors testified for the records and for the Sobibor war crimes trial of 1965.

Regina Zielinksi testified, recalling how they acquired the wool needed for the stockings. The girls had to unravel old knitted clothes removed from the gas chamber victims. Her testimony explained that they had to make the old wool new. “This way we started to knit. All the socks were for the soldiers. They had to be big and long and warm. We had to make at least one sock a day. So the knitting time wasn’t just from dawn to dusk. Sometimes it carried over as long as the lights were on, till about ten o’clock at night in the winter. Later on, it was a little longer.”

Regina married on December 24, 1945 in Wetzlar and settled in Australia on August 3, 1949. She told her story to her son Andrew, who published it in 2003 under the title ‘Conversations with Regina.‘

Regina said, “If you’re not a knitter like me, you may have never heard of World Wide Knit in Public Day (which actually spans one week every year). When people asked me what I did for WWKIP that year, I proudly said, “I went to the death camp at Sobibor, and I knitted my sock because I wanted to, not because my life hung in the balance. I knitted for the sock knitters of Sobibor whose names we don’t know and for those who survived incredible odds. I knitted for life. In remembrance there can be hope.”

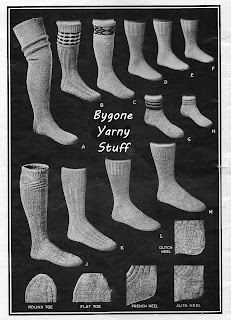

A knitted stocking from a 1933 British publication

In the 1940s and 1950s men wore stockings not socks, and Regina says the soldiers wanted them long and warm. Stockings reached the knee, and only children wore short socks. Stockings took a lot of knitting and would take around 8 ounces (200 g) of woollen yarn, so required around twice the amount of knitting as a pair of modern ladies’ socks. I wonder how many knitters today could knit a stocking in a day.

These girls evaded the gas chambers because they knitted socks.

(Information taken from www.jewsforjesus.org)

There is an online knitting and crochet organisation called Ravelry.com which has 4 million members. There is a page mentioning the knitters: https://www.ravelry.com/patterns/library/lizkor-remembrance-socks

More details of the WWII survivors can be found in https://www.holocausthistoricalsociety.org.uk/contents/sobibor/sobiborsurvivorsandescapees.html