"Bell-wether o' Barking, cries Baa, baa,

How many sheep have we lost to-day?

Nineteen we have lost, one have we fun,

Run Rockie, run Rockie, run, run, run.

"Bell-wether o' Barking, cries Baa, baa,

How many sheep have we lost to-day?

Eighteen we have lost, two have we fun,

Run Rockie, run Rockie, run, run, run." etc

Note that 'fun' is 'found', Rocky is the sheep-dog and Barking is a hill or a village. There is a youtube video of three Yorkshire ladies talking to a local audience about The "Terrible" Knitters of Dent in Yorkshire, and they sing this song.

I read in 'The Old Hand Knitters of the Dales' by Marie Hartley and Jane Ingleby, first published in 1951, that each line of the verse is a needle-full of knitting, and each verse is a full round, then by the time you eventually arrive at 'None we have lost ..." you have completed twenty rounds. If this is so then we are looking at 8 beats a line, so 32 stitches a round. No mass-produced commercial knitted product would have so few stitches. And English knitters always used 4 needles in a set; 5-needle sets have only been available in the UK since we started buying on-line from international manufacturers and stores.

To knit on four needles, you distribute your stitches across three needles, meaning two of the song's lines would need to 'join up' to cover one needle.

It would also seem probable that if the knitters were all knitting the same number of stitches per needle, they were all working on the same contract for the same garment. Gathering together no doubt helped to relieve the tedium of knitting so many identical garments.

There is another rhyme reported in the Hartley & Ingleby book. This is attributed to Cumberland, now part of Cumbria:

Bulls at bay,

Kings at fey,

Over the hills and far away.

You may observe that this rhyme has a rhythm of four or 16 beats, depending on whether you count a line of the verse as a 'needle' or whether you feel the whole verse is a 'needle'. Again, the same figure of 16 pops up. Sixteen stitches on two needles and 32 on the third gives a circumference of 64 stitches and this is a real possiblity for a stocking-type garment, which were knitted in their countless thousands at that time. The songs could be sung two stitches to each beat; the knitters were very fast! Knee-length and full-length stockings were basic knitting, but these were usually knitted to a finer gauge than 64 stitches a round, and recipes of over 100 years ago suggest that finer needles were routinely used and around 80 to 140 stitches cast on. Such small stitches might not really lend themselves to a communal evening squashed together in a tiny front parlour in the firelight. Fine knit over-the-knee length stockings of the day also narrowed as they approached the heel, meaning that the number of stitches would vary depending on your progress. This would not fit the idea of the whole roomful of knitters singing and working to the same regular rhythm.

I went off to search for a likely garment of 32 or 64-stitch rounds in the 19th Century. The same 'Yorkshire' book mentions bump-knitting with very coarse locally produced wool spun and plied in the grease knitted into enormous stockings with thick needles. The stockings, when completed, measured a yard (nearly a metre) long and the feet were 13 inches (33 cm) long. Hartley & Ingleby relate that children would wonder who or what could possibly wear such huge stockings, and would suggest it had to be elephants! Wondering where these enormous stockings ended up I discovered that these were scoured (washed and shrunk) in local mills, then dried on stocking-boards to give them extra thickness as well as a regular size and shape. These felted stockings would have been very sturdy and long lasting.Who wore these thousands of enormous stockings?

My husband's father, born in 1901, was a Newlyn master fisherman and in the days before modern waterproof clothing, he wore seaboot stockings under his oilskins (literally canvas coats brushed with water-repellant oil). These stockings were pulled over trousers and socks and enabled the wearer to pull his long leather or rubber seaboots on neatly while adding a layer of warmth. There is a photo on the back cover of Michael Pearson's superb book 'Traditional Knitting' of a fisherman wearing long seaboot stockings inside his thigh boots. (Incidentally, his basket contains hooks ready fastened to a 'long line', but safely stowed until required).

This book is a really good read. Mr Pearson gathered knitting stories, patterns and techniques from many fishing villages and towns.

This looked a real possibility for the 64 stitch garment. To knit this stocking you could utilise three needles with 16, 16 and 32 stitches on, and the 4th needle to knit in rounds.

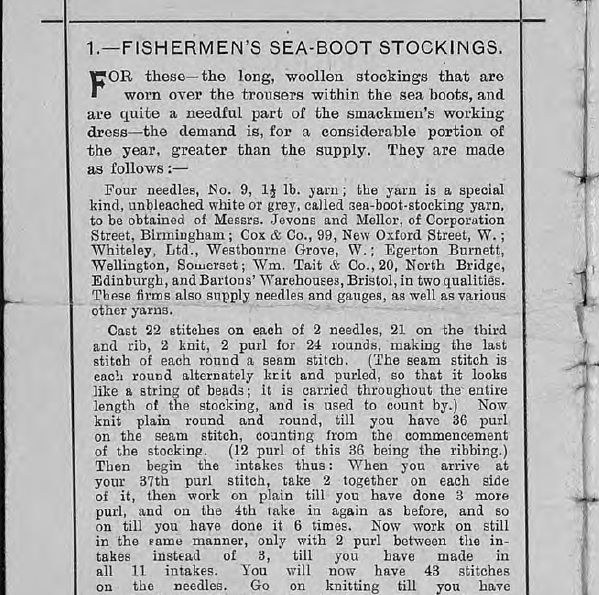

My next task was to find instructions for knitting them. I went to that excellent historical knitting library held by the University of Southampton and found a little book published for the Royal National Mission to Deep Sea Fishermen in the late 1800s . It gives instructions for knitting seaboot stockings (as well as many other sea-men's clothes). The yarn is described as 'carpet yarn' elsewhere so you can imagine how thick it was. There are 65 stitches in this version, but remove the 'seam stitich' and you have the magic 64 stitches which is knit straight for several inches before 'narrowing' for the ankle.The purled seam stitch was introduced purely to enable amateur knitters to space decreasings (intakes) by counting the purl-bumps in the 'seam'. I have on my computer at least two other contemporaneous books containing almost identical instructions.

This lovely little book was in the collection of His Grace the Bishop of Leicester, the late Richard Rutt, and donated to Southampton University. Anyone with an interest in 19th century knitting manuals may like to browse his historical knitting book collection (available free online). No 9 needles are today's 3.75 mm needles.

When the UK moved over to metric knitting needle sizes sixty years ago, some of the old sizes which were based on fractions of an inch did not translate exactly, so we discovered that our new needles were not quite the same as the old. If you should try knitting from an old UK pattern, bear in mind that your tension square may not quite match.

I have made a swatch from this seaboot stocking pattern, and the dimensions and instructions are relevant today, and would suit anyone who works in water, or any really cold conditions, the slight change in modern needle sizes over so few stitches makes no real difference.

The introduction in this book says that demand for these socks always outstripped supply, so no doubt there was a real market for the thousands of seaboot stockings, to be worn by countless thousands of fishermen and mariners. We know that local stocking knitters were kept supplied with bundles containing skeins of 'bump, and these seaboot stockings were what I believe our Yorkshire knitters were producing during their winter evening get-togethers.

If you would like to receive my newsletters by email once a month please email me through my website www.woollywoodlanders.co.uk - a link on nearly every page!

______________________________________________________________________________________

No comments:

Post a Comment